Rascals case in brief

In the beginning, in 1989, more than 90 children at the Little Rascals Day Care Center in Edenton, North Carolina, accused a total of 20 adults with 429 instances of sexual abuse over a three-year period. It may have all begun with one parent’s complaint about punishment given her child.

Among the alleged perpetrators: the sheriff and mayor. But prosecutors would charge only Robin Byrum, Darlene Harris, Elizabeth “Betsy” Kelly, Robert “Bob” Kelly, Willard Scott Privott, Shelley Stone and Dawn Wilson – the Edenton 7.

Along with sodomy and beatings, allegations included a baby killed with a handgun, a child being hung upside down from a tree and being set on fire and countless other fantastic incidents involving spaceships, hot air balloons, pirate ships and trained sharks.

By the time prosecutors dropped the last charges in 1997, Little Rascals had become North Carolina’s longest and most costly criminal trial. Prosecutors kept defendants jailed in hopes at least one would turn against their supposed co-conspirators. Remarkably, none did. Another shameful record: Five defendants had to wait longer to face their accusers in court than anyone else in North Carolina history.

Between 1991 and 1997, Ofra Bikel produced three extraordinary episodes on the Little Rascals case for the PBS series “Frontline.” Although “Innocence Lost” did not deter prosecutors, it exposed their tactics and fostered nationwide skepticism and dismay.

With each passing year, the absurdity of the Little Rascals charges has become more obvious. But no admission of error has ever come from prosecutors, police, interviewers or parents. This site is devoted to the issues raised by this case.

On Facebook

Click for earlier Facebook posts archived on this site

Click to go to

Today’s random selection from the Little Rascals Day Care archives….

Click for earlier Facebook posts archived on this site

Click to go to

Today’s random selection from the Little Rascals Day Care archives….

Is psychiatry ready to face up to its denial?

Feb. 1, 2014

Feb. 1, 2014

“As our medical schools and graduate programs fill with students who were born after 1989, we meet young mental health professionals-in-training who have no knowledge or

living memory of the Satanic ritual abuse (SRA) moral panic of the 1980s and early 1990s. To those of us old enough to have been there, that era already seems like a curious relic of the past, bracketed in our memory palaces behind a door we are loathe to open again.

“Some mass cultural phenomena are so emotionally-charged, so febrile, and in retrospect so causally incomprehensible, that we feel compelled to move on silently and feign forgetfulness…

“Despite the discomfort it brings, we owe it to the current generation of clinicians to remember that an elite minority within the American psychiatric profession played a small

but ultimately decisive role in the cultural validation, and then reduction, of the Satanism moral panic between 1988 and 1994….

“Are we ready now to reopen a discussion on this moral panic? Will both clinicians and historians of psychiatry be willing to be on record?”

– From “When Psychiatry Battled the Devil” by Richard Noll in Psychiatric Times (Dec. 6, 2013)

Wow! After more than two years of seeing mental health professionals shrug off responsibility for the moral panic they promoted, I can hardly believe what I’m reading. Noll, an accomplished author and professor, traces how it all happened – and asks, “Shall we continue to silence memory, or allow it to speak?”

An early vote to silence memory came from an unexpected source: Psychiatric Times itself, which clumsily pulled Noll’s piece from its website.

By contrast, Allen Frances, professor emeritus of psychiatry at Duke, offered a powerful – and I hope influential – personal mea culpa.

Edenton Seven could’ve used a Johnny Depp

Sept. 10, 2012

Sept. 10, 2012

“You saw those initial documentaries, you make a choice: Am I going to watch the thing and go ‘Wow, that’s really horrible,’ and go out and get a milkshake?”

– Johnny Depp, tracing the roots of his advocacy for the West Memphis Three

That could be me talking – except that the eye-opening documentaries for me were “Innocence Lost” rather than “Paradise Lost,” that I’m a retired newspaperman rather than a Hollywood actor and – most crucial – that I went out for a figurative two-decade milkshake run rather than responding immediately to the outrage I was seeing on screen. Hats off to WM3 advocates such as Depp, who moved quickly to challenge prosecutors every bit as recalcitrant as those in North Carolina.

‘I was aware of the possibility of childish fantasy….’

July 11, 2014

July 11, 2014

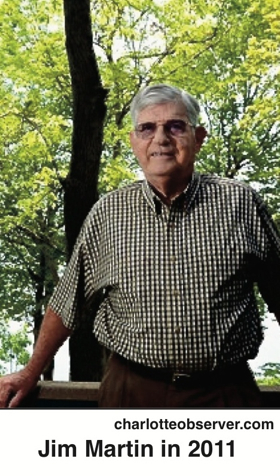

“…. As you might imagine, I had not had reason to think about the Little Rascals case until your email arrived. Yes, I was very interested in the case at the time, but had no role or authority to intervene. (See governor’s 1991 response to letter writers.) The arrests and charges were highly publicized, as were the proceedings of the trial, upon which the two accused were convicted. So, like most citizens, I felt a compulsion to follow the case, at least insofar as the news coverage.

“My recollection is that both the horrible accusations and the contrary indications of coached and imaginative testimony of the children were featured in the coverage…. Being very familiar with Arthur Miller’s brilliant drama, ‘The Crucible,’ I was aware of the possibility of childish fantasy passing as falsely condemning testimony. From a distance, most readers probably shared the concern, ‘What if it were true?’

“I do not recall whether the defense attorneys contacted my office in an appeal for clemency in 1991-1992. Had they done so, they would have been advised that my practice was to let the appellate courts complete their judicial review before considering clemency. This was complete in 1995 when the NC Supreme Court declined to review the finding by the Court of Appeals of trial error, at which time there would be no cause for Governor Hunt to intervene. I have great respect for the judgment and integrity of then Chief Justice Burleigh Mitchell, and that would settle the legal principles of the matter for me.

“I can only wonder what conclusion I might have reached had the appeal for clemency been properly before me. My approach in such cases was to meet separately with advocates on both sides, without restricting the nature or style of what they had to say. I would make my decision based on corroborated evidence and the trial record, without following its standards for disqualifying some evidence. I gave attention to two main standards: (a) whether the punishment was suited to the nature of the crime, and (b) whether there was doubt as to the guilt of the person convicted….

“I believe your cause is to persuade the Governor to issue a Pardon of Innocence for Bob Kelly and Dawn Wilson. It may be difficult to produce exculpatory evidence several decades after the events. You did not say whether Mr. Kelly and/or Ms. Wilson wish to return to that gauntlet, considering the degree to which they have restored their lives. If they do, it would my hope that Governor McCrory and his counsel would weigh the two guidelines cited above, although no Governor is bound in clemency matters by any precedent of his predecessors. While it can be difficult to prove a negative, it would help your cause if there were former accusers now in their thirties who have recanted the accusations of their childhood. Otherwise, the appellate finding of procedural error alone might not be sufficient.”

– From a letter from former Gov. Jim Martin responding to my question about his recollections of the Little Rascals Day Care case

As welcome as a gubernatorial pardon would be, my hopes for the Edenton Seven are more modest: a “statement of innocence” from the governor or attorney general similar to that given the defendants in the Duke lacrosse case.

If only the Little Rascals prosecutors had been as familiar with “The Crucible” as was the governor….

Veteran journalist bought into Believe the Children

Oct. 4, 2014

Oct. 4, 2014

Among those journalists who fell for the “satanic ritual abuse” storyline, none fell harder than Civia Tamarkin.

She not only stage-managed an embarrassingly credulous episode of “Nightline,” but also testified earnestly at a Believe the Children convention alongside Little Rascals prosecutor H. P. Williams Jr. and supposed ritual-abuse survivor Laura Buchanan (““ was told that a surveillance device would be inserted into my brain….”).

In 1993 Tamarkin delivered a lengthy address on “Investigative Issues in Ritual Abuse Cases” to the Fifth Eastern Regional Conference on Abuse and Multiple Personality in Alexandria, Va.

Like Ross Cheit two decades later, she had no trouble detailing numerous flaws in the prosecution of McMartin and other ritual abuse cases but inevitably came up frustrated in her search for a smoking gun or two. Most striking, after recounting all her journalistic fault-finding, was her unquestioning gratitude to SRA snake-oil theoreticians Roland Summit and Bennett Braun for “(taking) the time to teach me what they could.”

Prior to her affiliation with Believe the Children, Tamarkin had reported commendably for Time, People and the Chicago Sun-Times and had coauthored a book with Chicago educator Marva Collins.

More recently, she has directed a documentary on the aftermath of a soldier’s death in Iraq….

So what happened in the 1990s? How did an experienced reporter lose her skepticism in the face of “ritual abuse” claims?

I’ve asked Tamarkin what she was thinking then – and what she believes today – but haven’t received a response.

0 CommentsComment on Facebook